For most of their existence, special-purpose acquisition companies were mostly unknown. But this year, they’ve become some of the hottest investment vehicles on Wall Street, offering companies an alternative to a traditional IPO and opening up fertile new ground for dealmakers.

Entrepreneurs, business executives, hedge fund founders, politicians and sports executives have all gotten in on the act, launching new blank-check companies that are now hunting for acquisition targets. But few segments of the financial world have been as closely intertwined with the SPAC boom as private equity. Even an industry powerhouse with $414 billion in assets under management has joined the frenzy: On Wednesday, Apollo Global Management registered its own blank-check company with the SEC, with plans to raise $750 million.

For some firms that were early adopters, this year is the continuation of a longtime strategy. Other firms are dipping a toe into the SPAC pool for the first time. For veterans and newcomers alike, these deals have become a popular path to capitalizing on the market volatility driven by this year’s pandemic. Alec Gores, the founder and CEO of The Gores Group, told CNBC in August that, because they offer sellers flexibility, efficiency and better valuation certainty, SPACs have become a great way to get to Wall Street.

SPACs essentially function as shell companies, with no operations of their own. They first raise capital from outside investors in an IPO, and then later use the proceeds of that offering to acquire a private company in a reverse merger. The target company is still subject to certain regulatory reviews, but the process offers a simpler path onto the public market than the usual IPO roadshow—particularly now, when travel and in-person meetings are much more difficult. SPACs have existed since the 1990s but only began to come into vogue in recent years.

Few, if any, private equity executives are better positioned than Gores to speak to the growing appeal of SPACs. His firm launched its first blank-check company in 2015, raising $375 million that it deployed the next year in a merger with Hostess Brands. Gores has backed five more SPACs in the years since, including two that were active in August. That month, the firm raised $525 million from the IPO of a new vehicle, and one of its older SPACs lined up a $3.4 billion merger with Luminar Technologies, a developer of sensors for autonomous cars.

Busy summer for PE firms and SPACs

Other private equity firms have also been busy this past summer. RedBird Capital Partners teamed up with famed baseball executive Billy Beane—the man who inspired “Moneyball”—to launch a SPAC that will aim to acquire a professional sports team, raising $575 million in an August IPO. Days later, Solamere Capital, led by Tagg Romney, Mitt Romney’s son, announced plans to raise up to $300 million for a new SPAC formed in conjunction with former House Speaker Paul Ryan. And it was reported in late August that TPG Capital is planning a pair of SPACs, one focusing on tech and the other on social impact deals, that will total some $700 million.

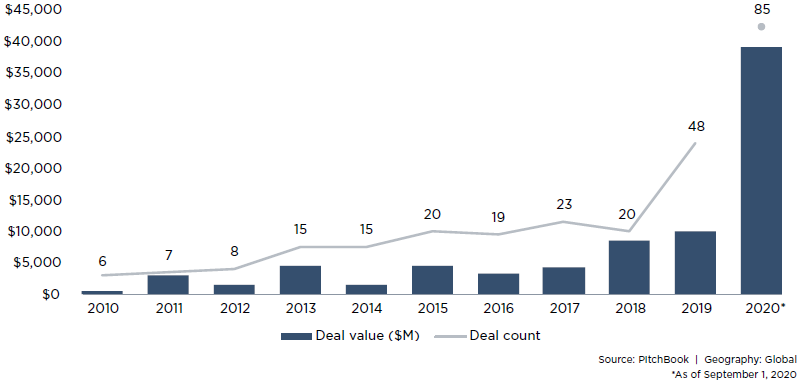

These new blank-check companies are contributing to a significant spike in SPAC deal count and capital raised. As of this writing, 85 different SPACs have gone public this year in the US, combining to raise more than $39 billion, according to PitchBook data. Those figures are already more than double the full-year totals for 2019, a year that had established new annual highs.

Why are SPACs popular with PE firms?

What’s making SPACs so popular, especially among private equity firms?

The structure of most reverse mergers means the deals require a more modest outlay than traditional buyouts. A private equity firm sponsoring a SPAC typically buys between 2% and 3% of the shares offered in its public listing.

“For the private equity firm, they get a large economic stake in the business for less upfront investment,” said Cameron Stanfill, a venture capital analyst at PitchBook who specializes in SPAC research.

SPAC registration in the US over the past decade

Private equity investors, of course, are very familiar with raising capital on the private market to finance future takeovers. In a SPAC, they instead draw from public backers, allowing them to broaden their investment base and eliminating the time commitment and other difficulties of raising funds from LPs.

The sponsors of a SPAC often line up an anchor commitment through a PIPE deal with an outside investor, offering possibilities for additional liquidity after the SPAC goes public. A recent example came when hedge fund Millennium Management purchased a 7.8% stake in RedBird’s sports-focused SPAC shortly after its IPO.

SPACs vs. traditional IPOs

“You’ve got a vehicle that already is poised for liquidity,” said Jeffrey Smith, a partner at Sidley Austin who specializes in SPAC deals. “It’s a public company. And your equity as a founder is structured in a way where, frankly, the warrants usually are exercisable within 30 days after the deal, and founder’s shares amounts to 20% of the size of the SPAC, which is very, very significant.”

SPACs also have plenty of appeal for potential targets. In a reverse merger, companies only need negotiate a price with one investor—the SPAC— rather than the wide range of prospective backers that comes with an IPO. That’s especially appealing against the backdrop of a stock market that has been historically volatile during the pandemic, when the misfortune of pricing an IPO on a bad day for the market could hurt the company’s valuation.

Founders also typically don’t have to give up as much control when merging with a SPAC compared to a traditional buyout. What’s more, several high-profile companies that have taken the SPAC route, including Virgin Galactic and DraftKings, have seen their stock prices surge since their respective mergers. For Smith, it all adds up to an impressive body of evidence.

“Why do a SPAC?” he said. “The economics are so good, it’s almost, why not do a SPAC?”.

Source: PitchBook

Can’t stop reading? Read more

Top private equity news of the week

Top private equity news of the week Goldman Sachs Asset Management (GSAM) has introduced a new...

Blackstone appoints Michele Raba to lead European private equity amid $500bn regional investment push

Blackstone appoints Michele Raba to lead European private equity amid $500bn regional investment...

Mutares expands Nordic footprint with acquisition of Sweden’s M3 Group

Mutares expands Nordic footprint with acquisition of Sweden’s M3 Group Mutares SE & Co. KGaA...